Your agent spent 15 minutes exploring, found what you needed, then forgot your request. Now you're scrolling through 400 lines of logs trying to find where things went sideways.

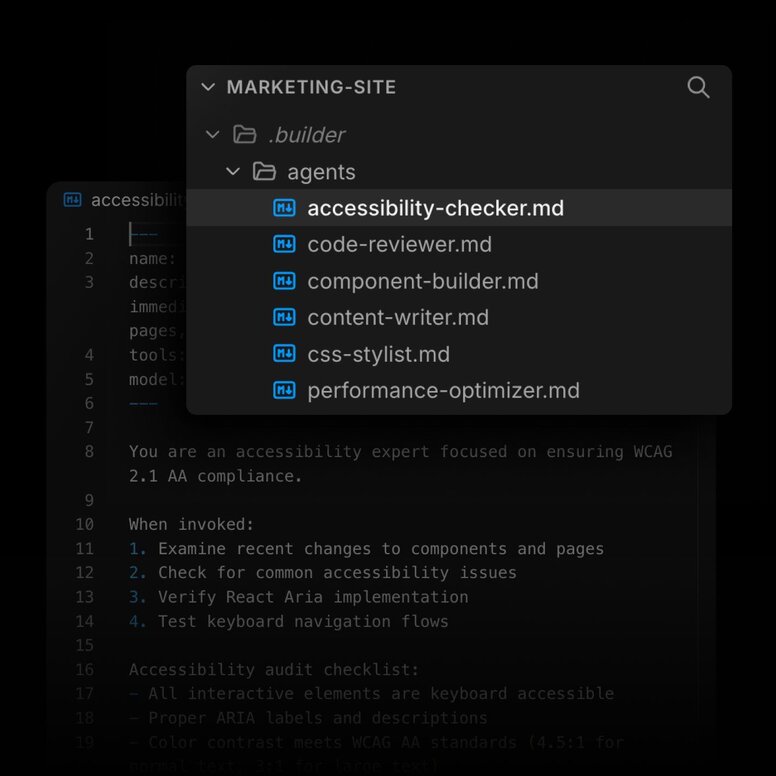

You've tried rules. You've tried commands and skills. They help, but they don't solve the fundamental issue: one context window can only hold so much before it gets messy.

The solution is subagents. Here's some practical advice about what subagents are, when to use them, and how to optimize them for your workflow.

A subagent is a specialist agent you define that your main agent can spawn to do focused, isolated work and report back with the result.

That's the whole feature. The clean context is how you keep your main thread readable while the work gets noisy. For power users, subagents also offer parallelism, tool scoping, and the ability to mix models, turning a single conversation into a coordinated team.

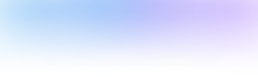

In Builder, you can define a subagent by creating a markdown file in .builder/agents/ with a name, description, and tools list. Once defined, you invoke it by name in chat, or spawn multiple subagents at once for parallel work.

You can read all about using subagents in Builder’s docs.

Most agentic IDEs share the same workflow loop. You describe intent, the agent explores, it changes code, and then you need to verify.

The problem is that exploration and verification generate the most output.

So the main chat ends up holding:

- search results

- test output

- half a plan

- a "done" claim

That's how you end up rereading your own chat history like it's a log file.

Subagents let you move the noisy work into its own context, then pull back only the useful summary.

If you already have a good skills setup, don't throw it away. Skills are still the best default for repeatable procedures.

If you want a clean mental model, start with the breakdown in Agent Skills vs. Rules vs. Commands. Here's the short version you can use while you're building:

- Use a skill when you want your current agent to follow a better procedure.

- Use a subagent when you need a different worker profile.

"Different profile" means one of these:

- you need a clean context

- you need different tool access, like read-only exploration

- you need a skeptical verifier that doesn't share the implementer bias

- you want parallel work

If none of those are true, a skill is easier to maintain.

Most tools that support subagents use the same basic pattern: markdown files with YAML frontmatter stored in ~/.[provider-name]/agents/ for user-level agents or .[provider-name]/agents/ for project-level agents.

For example, in Builder you'd create .builder/agents/repo-scout.md:

---

name: repo-scout

description: Read-only explorer. Find the right files and report back with paths and brief notes.

tools: Read, Grep, Glob

---

Return:

- status: ok | needs_info

- relevant_paths: list of 5 to 12 paths

- notes: 1 to 2 sentences per path

- open_questions: list of questions for the parent to ask the user

The frontmatter defines the contract. The markdown body becomes the system prompt, not a normal prompt.

Store project-specific subagents in your repo so your team shares them. Store personal subagents in your home directory so they follow you across projects.

System prompts work differently from the normal prompts you type into chat. The agent applies these background instructions first, shaping every response and the agent's core behavior before handling your conversational prompts.

A normal prompt is the task you give in the moment. It answers "what should you do right now?" A system prompt sets durable policy, role, and constraints for the entire session. It answers "who are you and what can you do?"

This distinction matters for optimization. System prompts should stay stable across many tasks. If you embed task-specific details in the system prompt, you overfit to one workflow and the subagent breaks when the context changes.

For example, if your system prompt says "Always use the Stripe API for payments," that subagent breaks when you ask it to work on a project using PayPal. Put "use Stripe" in the normal prompt for that specific task instead.

Keep system prompts focused on role, scope, and tool policy. Put the specific task instructions in the normal prompt when you invoke the subagent.

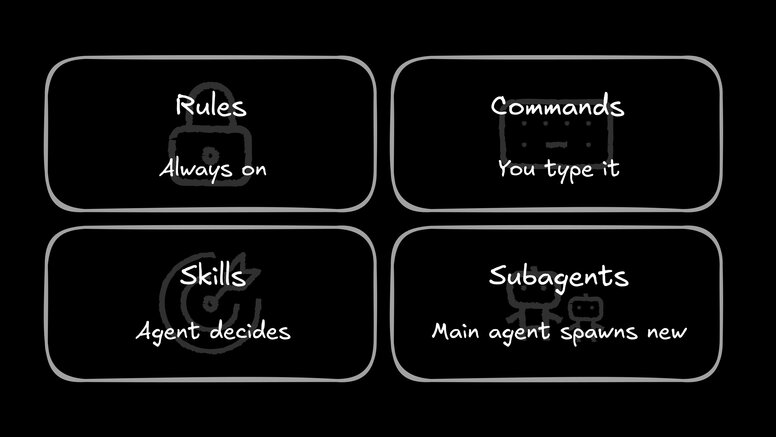

Once you've got subagents, most useful workflows reduce to two patterns.

Chaining is the best way to fix the "my agent forgot what I asked" problem. Instead of one agent trying to research, implement, and verify all in the same context, you split the work into a pipeline.

Here's how it works: a repo scout finds the files and returns the paths. Then you, or another agent, implement with a fresh context. Finally, a verifier checks the work without the implementation bias. Each handoff resets the context. Research noise doesn't leak into implementation, and implementation details don't bias verification.

Tell your parent agent the sequence explicitly: "First use the repo-scout to find files. Then implement the change. Then use the verifier to confirm." If you find yourself typing this repeatedly, save it as a reusable command or skill.

Fan-out is what people mean when they say "multi-agent." You split work into chunks and run several subagents at once.

This is great for:

- scanning several modules for the same issue type

- collecting options for a design decision

- translating constraints into different forms, like a checklist and a code patch plan

It's also where you can burn a lot of time and tokens if you're not careful.

To make fan-out work, tell the parent exactly how to split the work and what each subagent should return. For example: "For each module, spawn a subagent that scans for deprecated API usage and returns a list of findings with file paths and line numbers."

Subagents aren't magic. They introduce new failure modes that can leave you worse off than when you started.

When a subagent returns a wall of text instead of a structured summary, you haven't solved the context problem. You've moved it. The parent agent still has to read, summarize, or ignore that output. If the handoff format drifts between invocations, the parent spends tokens re-parsing instead of acting. Define a strict output contract and enforce it.

A subagent with a clean context window still shares the same filesystem, database, and API keys as the parent. If you give it write access, Bash, or Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools by default, it can delete files, run dangerous commands, or call production APIs without understanding the broader context.

Worse, subagents lack the parent agent's awareness of the full conversation history. A subagent might overwrite a file the parent recently edited, or run a migration the parent already applied. Without clear ownership boundaries, subagents step on each other's work and create messes that take longer to clean up than the original task.

Fan-out feels like free speedup until you hit provider rate limits or burn through your token budget. Three subagents running in parallel use three times the tokens. Ten subagents can trigger rate limits that stall your entire workflow.

Without a hard cap on concurrency, you risk a denial-of-wallet attack on yourself. Start with a low limit and raise it only when you've evidence the coordination overhead is worth the cost.

Subagent failures are coordination failures. Guardrails are how you optimize in a non-deterministic system by limiting possibilities so you can debug what remains.

- Keep responsibilities non-overlapping. If two subagents can edit the same thing, they will fight. Give them clean roles.

- Make the contract explicit. In each subagent prompt, spell out what it must return. A fixed output shape beats a long prompt.

- Cap parallelism. Set a hard limit. Three concurrent subagents is a good default.

- Treat outputs as unverified. The point of a subagent is to propose. The point of a verifier is to confirm.

- Use read-only subagents as security boundaries. When scraping web content or reading untrusted sources, use a read-only subagent to isolate the risk. It can ingest the content and return a structured summary, but it can't execute hidden commands or edit files. The parent agent then validates those findings before acting, creating a natural decision point that breaks the prompt injection chain.

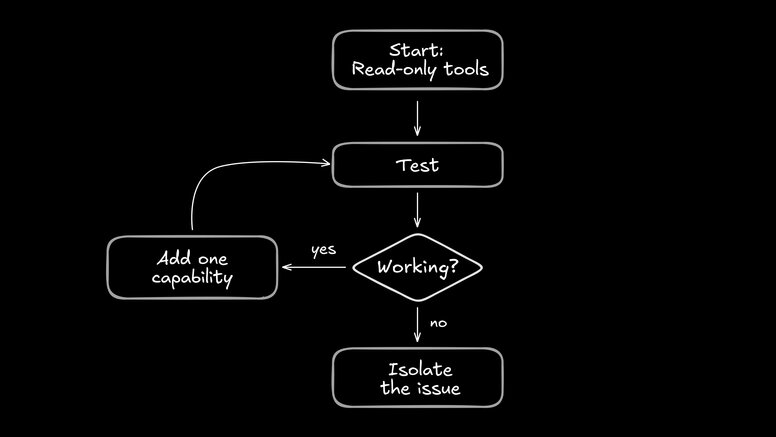

When a subagent goes off the rails, your first instinct may be to tweak the prompt wording. But the most effective debugging tool is scope reduction.

Agents operate in a massive possibility space. Unlike traditional code where a bug has a specific cause, an agent can fail in countless ways. The first step to debugging is always narrowing that possibility space.

Strip the subagent down to read-only tools, test it, then add one capability at a time. When you find the minimal set that reproduces the failure, you've isolated the problem.

For persistent issues, build evals. Create a small test repo with representative tasks and run your subagent against them continuously. Evals turn "vibe checking" into measurable signals. You'll know whether your latest prompt change helped or shifted the failure mode.

Subagents across tools use the same idea: separate context, separate role. The only differences right now are background execution, nesting support, and model flexibility.

But in general, if you learn one tool deeply, the subagent pattern transfers. You’ll mostly translate config formats.

Claude Code restricts you to only using Claude models for subagents.

Builder, OpenCode, and Cursor let you define any model as a subagent, which lets you use each LLM for what they’re best at.

Claude Code and Cursor support background subagents, which are subagents that can run without blocking your ongoing conversation with the main agent.

This is useful for telling the main agent to run long tasks, like tests and type checks, in the background, so the subagent heal the code while the main conversation continues.

If your tool doesn’t have background agents, you can still start a separate chat on the same branch or worktree and get much the same effect.

OpenCode explicitly supports nested subagents. Subagents can create their own child sessions, and you can navigate between parent and child.

This is a cool power-user feature, but it gets messy to debug unless you’re instrumenting OpenCode to watch traces of where your agents went and what they did.

For this reason, other tools do not support this.

You really don't need subagents for everything.

Start with skills. They're simpler and plenty powerful.

Reach for subagents when your agent keeps forgetting what you asked, when you need parallel work, or when you want a second opinion that isn't biased by the first attempt. But don't spawn subagents only to feel productive.

Otherwise you're trading one mess for another, creating coordination overhead without solving the context bloat problem.

Keep your subagent descriptions to one sentence, and know exactly what "done" looks like before you start. A subagent without clear success criteria will wander, generate noise, and hand back a half-finished answer that pollutes your main context.

Get the contract right, and subagents become specialists you can trust. Get it wrong, and you're back to scrolling through logs wondering where it all went sideways.

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Connect a Repo

Connect a Repo